If economists made a list of the things they agree on, free trade would be at the top of the list. Unfortunately, economists don’t talk much about what they agree on. They only debate their disagreements at the margin. That leaves the public and their congressional representatives with the impression that since the professionals don’t agree, their instincts are as good as any on the subject.

That’s dangerous because of the fallacy of composition, which you get into when you generalize from personal experience. What’s true for the individual is rarely true for the nation as a whole. For example, money represents wealth for its individual owner but not for the nation as a whole. That was the point of Smith’s Wealth of Nations, which was an argument against the mercantilist protectionists of his time and an argument for free trade, both internal and external.

One problem with the arguments for free trade is that its benefits are diffused among the many and its harm is concentrated among the few. Those harmed by freer trade are fewer in number, but they know who they are. The many who are helped are generally helped less, and they don’t know what they have at stake. It’s an ideal situation for political pandering and demagoguery.

One of the most troublesome fallacies making free trade a hard sell is the fallacy that it causes job losses. It’s true that some jobs are lost and that other jobs are created. The jobs lost will be those that existed because of protection in areas of comparative disadvantage. Those gained will be those in areas of comparative advantage. The greater specialization coming from trade will increase total output in both trading nations. If society chose to do so, it could compensate the losers with the gains of the winners and have much left over.

Freeing up trade doesn’t change the number of jobs; it changes the mix of jobs, for the better. It’s an oversimplification, but assume that increased imports cost jobs in import-competing industries. And assume that increased exports create jobs in export industries. The thing to remember is that exports and imports change together and produce nearly offsetting changes in jobs.

When we import more, other countries have more money to buy our exports. When we export more, we get more money for imports. Exchange rates will adjust to keep those flows approximately the same. If exchange rates are fixed, the governments involved will have to provide compensating finance to maintain the balance.

One problem is that much of international trade theory and much of economics in general is counterintuitive. A wise man once said that if economics made sense, we wouldn’t need economists. Much of it seems not to make sense.

For example, Abraham Lincoln was a very good amateur economist. But he wasn’t good enough to get international trade right. Here’s what he is supposed to have said about tariffs: “I don’t know much about the tariff, but I know this. If I buy a coat in England, I get the coat and England gets the money. If I buy a coat in America, I get the coat and America gets the money.”

Every cab driver in the world would agree with that statement, but it’s wrong. Free trade is one of those economic ideas that is always proven right, but still fights to be accepted because it is so easily misunderstood.

Free trade is good. Protection is bad. Protection can benefit a few people, but at the expense of everyone else. Adam Smith said, “It is the maxim of every prudent master of a family never to make at home what it will cost him more to make than to buy.” This is also true of nations. If we can buy something cheaper abroad (in this case labor by the hour), we should buy it there and make something else here.

What Mr Lincoln failed to consider was that when he bought the coat in England, someone in England would spend the proceeds in America, possibly on Texas cotton to make the coat. The bucks don’t stop. You can’t have one-way trade. If other countries won’t buy from us (or lend us money), we can’t buy from them. If we won’t buy from them, they can’t buy from us.

If we impose tariffs or quotas on steel imports, we may be helping a steelworker, but it will be at the expense of other U.S. workers—possibly farmers—who won’t be able to export because the foreign country couldn’t sell its steel here.

To protect some workers is to harm others. The problem is those protected know who they are and what they have at stake. The person harmed has no clue. Which one will be writing his congressman?

The most effective rhetoric against protectionism in the history of the world was used by my hero Frédéric Bastiat, who was a self-taught economist and a member of the French Parliament in the 1840s. Bastiat wrote—tongue in cheek—a petition to the chamber of deputies on behalf of the French candle makers wanting relief from the unfair competition of the sun. Listen to this:

A Petition

From the manufacturers of candles, tapers, lanterns, candlesticks, street lamps, snuffers, and extinguishers, and from the producers of tallow, oil, resin, alcohol, and generally of everything connected with lighting.

To the honorable members of the chamber of deputies

Gentlemen:

You are on the right track. You reject abstract theories and have little regard for abundance and low prices. You concern yourself mainly with the fate of the producer. You wish to free him from foreign competition, that is, to reserve the domestic market for domestic industry.

We come to offer you a wonderful opportunity for applying your…practice….

We are suffering from the ruinous competition of a foreign rival who apparently works under conditions so far superior to our own for the production of light that he is flooding the domestic market with it at an incredibly low price….

Bastiat is referring, of course, to the sun. He asks for a law requiring the closing of all windows, dormers, skylights, inside and outside shutters, curtains, etc. Virtually all industries in France would benefit. There would be enormous multiplier effects, creating many new jobs and improving the national defense.

When I moved to Texas almost 10 years ago, the superconducting supercollider was just beginning construction. From reading the newspapers, I couldn’t figure out what it was supposed to do. All the emphasis was on the number of jobs it was going to create. It may have been a good idea. But if it was, it shouldn’t have been sold as a job creator.

My wisdom on jobs is this: If you want more jobs, replace all the bulldozers with shovels. If that doesn’t get you enough, replace the shovels with spoons.

No, jobs are too important to waste. You shouldn’t count jobs; you should make jobs count.

Actually, economic progress can be measured by job losses. It once took almost 90 per cent of our population to grow our food. Now we grow more food with less than 3 per cent of the population. Was that progress? Not if you measure progress by the job count. Progress is measured by productivity—output per hour worked—not by how many hours were worked.

What happened to farming yesterday is happening in manufacturing today. U.S. manufacturing today is very healthy. Its productivity is growing by leaps and bounds. That means that job growth in manufacturing is not keeping up with output growth. But that’s a good thing. That’s productivity growth.

The new jobs not being created in manufacturing are being created in our growing service sectors—in our new information/knowledge economy.

Back to free trade rhetoric. After Bastiat’s, the next-best free trade rhetoric I’ve found comes from Henry George, who is alleged to have said that protectionists want to do to their country in peacetime what the country’s enemies want to do to it in wartime: shut its borders to imports.

The arguments against free trade are similar to arguments against new technology. Both trade and technology offer you more total output. Both involve many winners winning a little and a few losers, each potentially losing more. In both cases, their enemies know who they are, but not their beneficiaries.

Listen to this letter, written by Martin Van Buren, the governor of New York in 1829, and see if it doesn’t ring true today:

January 21, 1829

To: President Andrew Jackson

The canal system of this country is being threatened by a new form of transportation known as “railroads.” The federal government must preserve the canals for the following reasons:

One. If canal boats are supplanted by “railroads,” serious unemployment will result. Captains, cooks, drivers, hostlers, repairmen and lock tenders will be left without means of livelihood, not to mention numerous farmers now employed in growing hay for horses.

Two. Boat builders would suffer and towline, whip and harness makers would be left destitute.

Three. Canal boats are absolutely essential to the defense of the United States. In the event of the expected trouble with England, the Erie Canal would be the only means by which we could ever move the supplies so vital to waging modern war.

As you may well know, Mr President, “railroad” carriages are pulled at the enormous speed of fifteen miles per hour by “engines” which, in addition to endangering life and limb of passengers, roar and snort their way through the countryside, setting fire to crops, scaring the livestock and frightening our women and children. The Almighty certainly never intended that people should travel at such breakneck speed.

Martin Van Buren

Governor of New York

I said earlier that Abraham Lincoln was a pretty good amateur economist, although not good enough to get trade right. I thought of him when I read about the window breakers in Seattle who wanted, among other things, to help the plight of poor people in poor countries by refusing to trade with them. By not trading with them, we’re somehow going to improve their environment and reduce the problem of child labor. Somehow, the problems of the world are caused by large corporations that employ people and by the free enterprise system that has produced unheard of wealth.

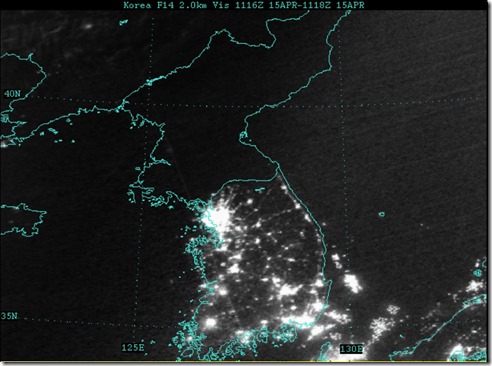

Instead they want the system that North Korea chose and left South Korea to languish in free enterprise. They prefer the advantages that East Germany had over West Germany. They want the pristine air and water found in the parts of the world not sullied by raw capitalist development—places like the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe.

I don’t have a clue how to argue with that kind of logic, the logic that has college kids all over the world trying to help child workers by taking their work away and their parents by refusing to buy their goods. I suppose parents in poor countries are not good parents. They need our moral superiority and guidance. We need to remove their temptation to let their children work by removing the market for the fruits of their labor.

As I said, for some reason I think of the economic wisdom of Abraham Lincoln when I think of the window breakers in Seattle and the trashers of McDonald’s in Europe.

Source: Bob McTeer, Remarks before the World Affairs Council and Texas International Trade Alliance, Houston, Texas. Oct. 10, 2000